AIM13 Commentary - 2020 Q3

“Life isn’t black and white. It’s a million gray areas...”

It is always hard to form a perspective on events as they unfold, and time will only tell how history judges our collective response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In our view, it has brought out some of the very best and worst of human behavior. While a lot of progress has been made, including with the recent positive news about vaccines, we still have a long way to go. We can definitely see a light at the end of the tunnel but, for now at least, we are still very much in the tunnel. As such, we must not let our guard down.

One lesson this experience has re-affirmed for us is that when one is in the middle of a situation, often there is no black and white and rarely only one path to take. This lesson reminds us not to look at all things through a binary lens – both with respect to the current crisis and how we approach investments and managers. This is not easy in a polarized world, and too often investors (and voters) take the easy way out and conclude quickly that an opportunity or manager (or candidate) is either “good” or “bad” – black or white – without doing the work necessary to arrive at an informed opinion. In this letter, we discuss how investing is about working through the “gray areas” to arrive at a decision – and then moving forward with conviction aware of what we know and what we do not know.

* * *

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

Life and investing would be a lot easier if solutions were easy to find and things were black and white. We would not need to spend as much time deliberating, asking questions, and turning things over in our mind before making a decision. While finding good managers may not be as difficult as inventing the record player, we often feel like Thomas Edison in the photo above – spending more time figuring out what is wrong rather than what is right. Unfortunately, a lot of investors take the simpler “black and white” approach to evaluating investment opportunities and managers. When there is an investment opportunity in the gray area – one that might fail a simple “check the box” approach – a lot of investors just walk away.

We have seen a similar bifurcated view in the way a lot of people have dealt with the pandemic. We have heard many describe those who follow the CDC guidelines as scared, frightened or overly cautious.

Others see people resuming their lives by eating at restaurants and going on trips as reckless or not caring about other people. We do not feel that it is so black and white. There is a lot of gray area in these decisions. Our conservative nature in investing makes us equally conservative when it comes to personally addressing these questions. People who are working to re-establish normalcy (while following experts’ advice) are not necessarily reckless. However, those who disregard simple precautions to prevent the spread of the disease because they see it as black or white – that is, “If I contract the disease, it will not impact me” or “I am not changing my way of life” – do not see (or do not want to see) that it can negatively impact many others.

People often tend to see what they want to see, and their biases shape what they want to see. This also leads to viewing things as black or white. For example, we think an over-simplified (and widely desired) view developed about disinfecting surfaces. In the beginning of the pandemic, a lot of us were wiping down anything that came into our homes. Then we were told that transmission was “primarily” through the air, and most people put away their Clorox wipes. However, the guidance was not so black and white. When the CDC says, “Spread from touching surfaces is not thought to be the main way the virus spreads,” they are not excluding surface transmission. The risk may be lower, but it still exists. Although a lot of people wanted to believe they did not need to wipe down anything, it is not so black and white, and we continue to take precautions.

We work to be aware of our biases (we all have them) and to avoid blindly accepting the easy answer. Investors often shortcut their analysis by focusing on simple indicators to form an opinion of a manager. Most obvious is the outperforming manager. If a manager is doing well, then investors conclude the manager is smart. Likewise, the allocators who invest with the manager congratulate themselves and think they are brilliant to have picked the manager (which is what they always wanted to believe in the first place). This, in turn, leads the allocator to give the manager more leeway. An investor may also have developed a friendship with a manager which makes it more difficult to redeem – and even more so when the manager is outperforming. This is why investors often redeem after poor performance and add to their winners. However, it is not that simple. We spend time figuring out why a manager is outperforming or underperforming. Often we have added to underperforming managers and redeemed from our better performers. We want to understand the “gray area” of why is the manager performing the way they are. This is not always an easy thing for allocators.

One thing we constantly push ourselves to do when investing with a manager is to identify at least three or four reasons why we should not invest. If we are unable to come up with those reasons, our concern is we are missing something. Rarely is something “guaranteed” with no downside. We also work hard to push ourselves to not celebrate when things are going well but instead spend time asking ourselves, are we doing a great job or are we just lucky? No matter how good an allocator can be, there is always some luck, and too many people confuse a bull market with brainpower.

“Skepticism is the highest of duties; blind faith the one unpardonable sin.”

When it comes to manager selection and oversight of our current managers, we strive to be ruthless skeptics and critics. Good investment managers will tell you that every day they own a stock they ask themselves, if they did not own it, would it be a buy? Similarly, whenever we have the opportunity to redeem from a manager, we ask ourselves if we were not invested, would we invest? Here are some of the other ways we work through the “gray areas” of investing and apply this skepticism to arrive at our investment decisions:

References, references, references: We often say, “past performance is not necessarily indicative of future returns – unless you are talking about someone’s character.” Reference checks are a cornerstone of our investment process, and we think we receive the greatest insights about a manager from others we respect who have known or worked with the manager. The mutual friends, the college acquaintances, the former work colleagues – much less the other investors who have invested with, or evaluated, the manager – are all invaluable sources of perspective about a manager. Moreover, we will perform cold references but we prefer to find ways to make them warm, conducting “references on references” – a further layer to reinforce our view of a manager. This takes a lot of time, with AIM13 reference checks on some managers exceeding 100 calls.

“If you tell the truth, you don’t have to remember anything.”

Manager Q&A: Whenever we are with a current manager or doing diligence on a new manager and the team, we try to ask the same question in different ways, at different stages in the process, and to different members of a manager’s team. While sometimes it makes us feel like the five year old who keeps asking the same question, we have uncovered discrepancies and inconsistencies that point us to either a fundamental issue or lack of shared vision among a manager’s team.

Trust but verify: As we describe above with respect to qualitative research and reference checks, for quantitative research and portfolio analysis, we use multiple sources, such as manager tear sheets, 13F and other public filings, prime broker reports, contacts at trading desks, and audited financial statements to triangulate portfolio data. For instance, we have compared onshore and offshore audited financial statements and found portfolio discrepancies, even though the manager tells us that the entities are run parri passu. All of this is more work than just relying on a risk metrics aggregator (we use one too), and it takes time. However, not only does this allow us to better verify what a manager is doing with its portfolio, it also has uncovered operational and reporting issues. For example, we have seen managers’ portfolio quarter-end marks mispriced on their 13F filings. This can be a simple error or lead to something much more troubling.

The devil is in the details: Whenever we can, we run document comparisons of a manager’s marketing materials, legal documents, and investor reports to see changes from one version to another. Sometimes we pull old materials from years back, and we see some interesting evolutions of how a manager positions itself over time. The changes may be minor but nuanced, and they often illustrate shifts that are important to understand. One area that provides a lot of insights is the footnotes; too often a document comparison highlights a meaningful change buried in fine print. Examples include changes to a manager’s AUM calculation, such as adding SMA’s that were not disclosed to us, or adjusting reported returns to account for new, lower fees that have been privately given to certain investors and improve the reported net return profile.

“An informed patriotism is what we want.”

We strive to be an “informed investor” which involves digging through the gray areas – the muddy waters – as well as not taking things at face value. Doing the work above, among a lot of other diligence we do, forms the “mosaic” of information that drives our decision-making. Mosaics, by their nature, are not black and white. at the end of the day, however, as we tell our analysts, “the road of life is paved with flat squirrels who couldn’t make a decision.” Once we have all of our inputs, the gray of uncertainty must give way to a defined course of action, which we can take with conviction knowing we have done all we can under the circumstances, and we know what we do not know.

Why Short?

Many investors have given up on shorting for a lot of reasons. Shorting is much harder than long investing. Not only do you need to get the analysis right, timing is much more important than going long a stock. The cost to borrow, especially with hard-to-borrow stocks (which often are the best ones to short), can quickly erode returns, even if you get the thesis right. Moreover, the upside is capped (a stock cannot go below zero), and the downside is theoretically infinite. Finally, larger managers have greater challenges since capacity for short positions is almost always constrained, and therefore even a productive short can provide little attribution to the portfolio’s overall return.

Of course, echoing what we say above about our investment process, just because something is hard does not mean you should not do it. Shorting remains an important part of our portfolio management, and we are constantly on the lookout for managers that can do it well. Just as managers and investment opportunities are not black and white, neither are markets and equity returns. We do not know the future, and so we cannot say if it makes more sense to be fully long or fully short, or to be on the sidelines in cash.

One episode this quarter illustrates the opportunities for managers who can short well. On September 8, GM announced a partnership with Nikola Corporation, a producer of zero-emission vehicles. Nikola’s stock shot up over 40% on the news. Then just two days later a short seller made the case that the company was misleading investors, and the stock plunged. The CEO resigned eleven days following, though GM says that it conducted “appropriate diligence.” Charlie Bilello Tweeted on September 20, “Just your average day in Nikola: +11.4% in regular trading, -10.3% in after hours. This market is becoming more like a casino every day.” As of this writing, the stock remains down over 70% from its high in June.

It is important to have conviction, but it is equally important to recognize the limits of what we can guess will happen in the future. Therefore, we believe that a material part of our portfolio should be “hedged” through short investments since it provides protection against what we think is the greatest threat to long term returns: permanent loss of capital. At the same time, we hope that our hedged investments underperform our overall portfolio because that means the market – and the majority of our portfolio – is going up.

Market observations

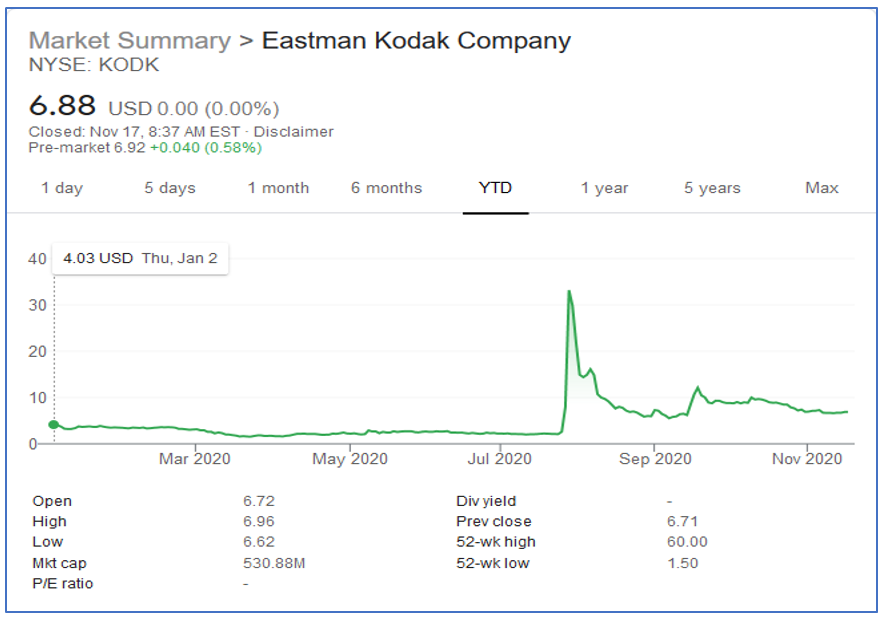

Few stock charts capture the pockets of irrationality of 2020 like Eastman Kodak’s, whose stock popped roughly 1,500% on news this quarter that the company received a loan to repurpose its facilities to make pharmaceuticals:

We were asked at the time, what were investors thinking buying in at its peak, only to lose 50%+ within about three trading days? The answer is that investors were not thinking, they were speculating. When Hertz issued up to $1 billion in equity in June while going through Chapter 11 bankruptcy, we knew that investors were reaching very far for returns.

Looking beyond the dislocations of 2020, we are watching several trends that will have profound impacts on the markets here and abroad over the near and medium term:

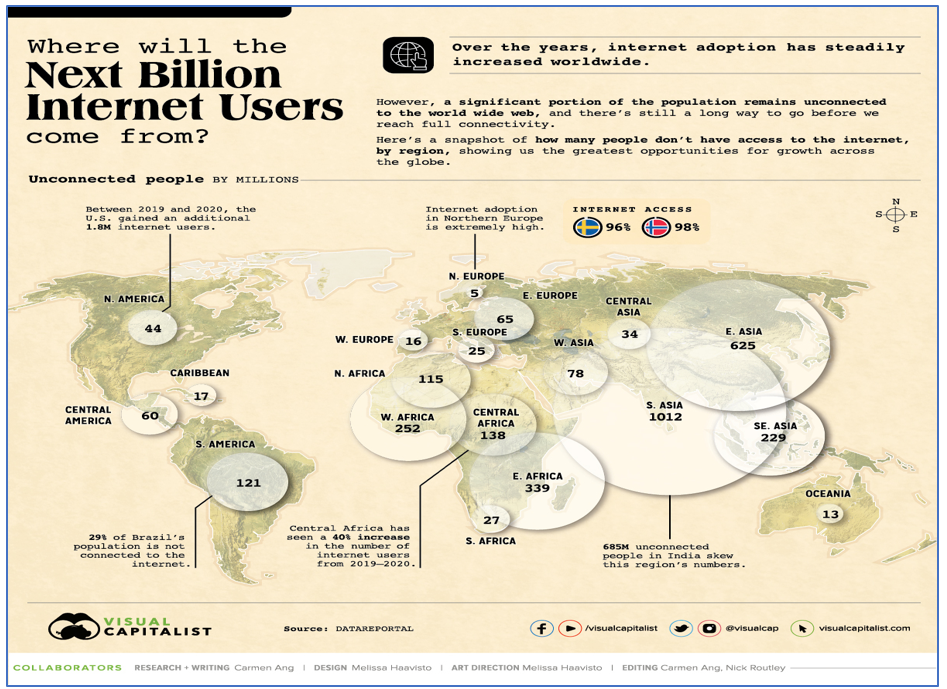

The Growth of Internet.

Source: Visual Capitalist, August 11, 2020

Not many people realize that over 40% of the world’s population is still not connected to the Internet. Put in more stark terms, UNICEF released a report in August that found that at least one third of the world’s schoolchildren cannot access remote learning online. Fortunately, these numbers are going down fast: according to Our World in Data, on any day in the five-year period ending in 2016, there were on average 640,000 people online for the first time. That is almost 27,000 new users every hour. When we read that the average person spends over six hours on the Internet everyday, it is fair to say that we have not yet seen the full power of the Internet and what that will bring in terms of efficiency, productivity and – let’s hope – global cooperation.

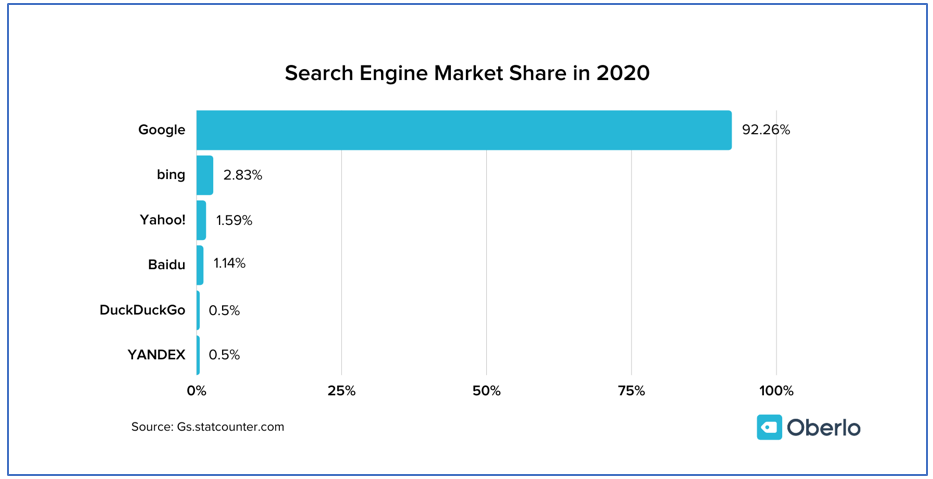

Potential Break Up of Big Tech.

Source: Gs.statcounter.com

With the growth of the Internet has come the emergence of the mega-tech company (the “Big Five”), whose soaring stock valuations have been the main driver of equity market returns over the last decade, as we discussed last quarter. Even the pro-business Forbes magazine ran an article on October 9, 2020 expressing the view that “mounting evidence suggests that the Big Five maintain their dominance thanks to insufficient regulation, anticompetitive behavior and business models that manipulate users.” President-Elect Joe Biden’s victory and a rash of recent antitrust lawsuits here and in Europe will increase the pressure to split apart these companies. Whether that would bring benefits associated with more competition (or even, as some suggest, help combat climate change!), is an open question but one with profound consequences.

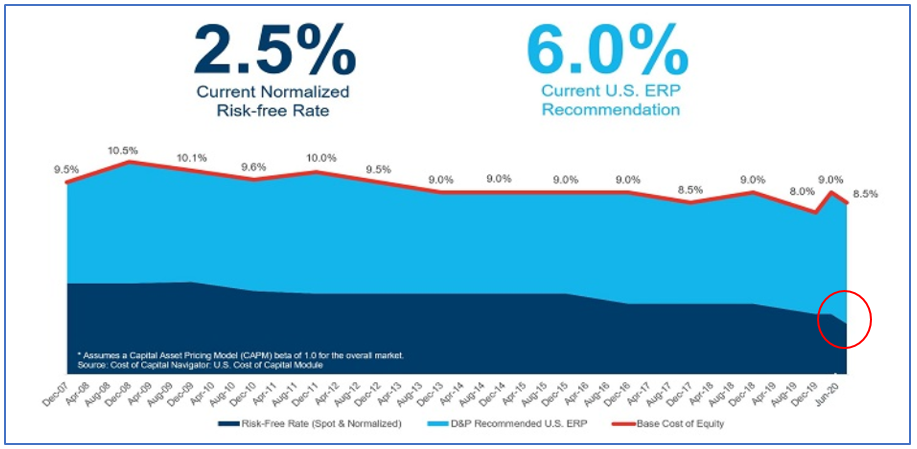

· Risk Free Rate.

Source: Duff & Phelps

On July 9, 2020, Duff & Phelps lowered its Normalized Risk-Free Rate to 2.5%, its lowest level in decades, given declining estimates of real interest rates and lower long-term growth estimates for the U.S. economy. With the yield on a U.S. 10-year Treasury Bill currently in a band of about 0.6% to 0.8%, and inflation forecast to be in the region of 2% over the course of the next ten years, investors in the “risk-free” rate are actually losing money should they hold such bonds to maturity. Likewise, strategists at J.P. Morgan wrote in October that the total stock of developed nation sovereign debt with a negative real yield now stands at $31 trillion. That is twice the level from two years ago and equates to 76% of total developed nation sovereign debt, up from 57% in 2017. As reported in the National Review on October 13, 2020, when put into the context of financial history, “the phenomenon of nominal interest rates below zero was virtually unprecedented in the 4,000 years of financial history prior to the current cycle,” according to financial historians Sidney Homer and Richard Sylla. This environment of unnaturally low rates cannot last forever, and when a “reversion to the mean” eventually occurs, a lot of companies and investments will suffer.

Closing Thought

“Bob Dole and myself do not see Al Gore and Bill Clinton as our enemy. We see them as our opponents. This is the greatest democracy in the world. People are watching not only throughout this country, but all over the world as to how this democracy can function with civility and respect, and decency and integrity.”

On the heels of one of the most contentious presidential campaign seasons in American history, we need to remind ourselves, as we do with our investments, to avoid “black and white” thinking in the political arena. Since we do not have anything to add to the discourse about the election, we have not offered much in these pages on the subject. What we can observe is that the two candidates presented starkly different alternatives, not only in their character and style, but also in important areas such as the economy, tax policy, healthcare, and racial and ethnic equality. Remarkably, the popular vote of over 140 million votes split almost right down the middle. This tells us that voters are roughly equally drawn to two almost diametrically opposed visions. However, as Jack Kemp expressed above, we must guard against an “us versus them” mentality. The best way forward, in our opinion, must be in the “gray area” in between the extremes, where solutions that address a broad base of concerns exist. To find these solutions will take hard work and time, and, just like investment diligence, the approach should not be binary. We remain confident that, with Jack Kemp’s “civility and respect,” the country can and should find the common ground solutions to move forward.

We welcome any questions or thoughts you may have. Please stay safe and well.

Alternative Investment Management, LLC (AIM13)